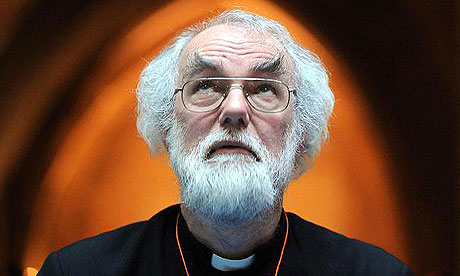

Time to say something nice about Rowan Williams; here goes.

Rowan has written about Dostoevsky, one of my favourite authors and, in spite of Rowan’s talent for making what is simple complicated, he does have some useful insights. From the Guardian

Why was the moment when Jesus, perhaps out of compassion for the tormented Inquisitor, kisses the man and then is allowed to slip from his cell into the Seville night, possibly never to be seen again, so important for Williams? “Dostoevsky has no easy answers, but what struck me when I first read the Grand Inquisitor episode was there is absolutely no form of words that can give a solution to suffering. Absolutely none. That’s why what ends the arraignment of the captive Jesus by the Grand Inquisitor is silence – and then Jesus kisses him. When I read it I had the dim sense that there was something very important in that what you look for in faith is not solutions but a certain relationship.” And that’s why Dostoevsky’s appeal has endured for Williams: he offers no closure, no authorial master-voice, but an endless dialogue where no one wins the argument but everyone is connected. In the book, he writes that Dostoevsky’s fiction is like divine creation, “an unexpected unfolding with no last word”. That might make divine creation sound akin to natural selection, but it’s how Williams sees God’s universe.

I thought I’d start with a bit where Rowan gets it at least partly wrong. While the Grand Inquisitor is about the problem of suffering, it also focuses on the idea that the institution of the church – and in particular the church hierarchy symbolised by the Inquisitor – sees its job as a salve to man’s chief source of suffering: his freedom. Man’s freedom is a recurrent theme in Dostoevsky and is, in his view, a major cause of human suffering. In Crime and Punishment Raskolnikov murders to demonstrate his freedom (to make himself ‘god’); we, too indulge in evil (usually less dramatic) to prove we are free – free from a God who wishes to constrain us. Even for a Christian, freedom can be a source of torment, since it is still possible for a Christian to sin. The Church will cheerfully relieve us of our God-given freedom by replacing it with an ecclesiarchy and, thus, make life – easier. Nevertheless, Jesus did come to truly set us free, not to make life easier. I suppose I can see why Rowan would not want to dwell on that.

Dostoevsky is renowned for his remark, “Without God, everything is permitted.” Does the archbishop agree? “He’s saying not so much that without God everyone would be bad, as without God we have no way of connecting one act with another, no way of developing a life that made sense. It would really be indifferent whether we did this or that. And it’s that sense of God being part of what you draw on to construct a life that makes sense.”

I agree with Rowan’s interpretation: without God life is meaningless, as are ethics, good and evil. This is a big problem for people like Dawkins and Hitchens who do not live up to their own dogma and behave as if their strutting and fretting has significance.

“In The Idiot, Prince Myshkin says, ‘When I hear atheists talk about Christianity, I don’t recognise what they’re talking about.’ I often feel when I read Richard Dawkins or Christopher Hitchens that this isn’t quite it. I thought it might not do any harm to put down a marker about that and say: ‘Here is a form of Christian engagement with the world and with the complexities of human experience that may be radically wrong but is not cheap or glib and any critique has to deal with this just as much as it has to deal with a southern baptist.’

He also tilts in the book at the pretensions of science, and by extension scientists such as Dawkins: “Science is a set of brilliantly successful methods producing brilliantly successful hypotheses about how things work. What it’s not is a picture of reality. It will give you a very significant purchase on reality. But it’s not an ethic, not a metaphysic. To treat it like that is a kind of idolatry.”

True: science describes a mechanism, not reality. For reality one must look to religion.

So, you see, I don’t think Rowan is merely a hairy old Welsh wind-bag. He has a redeeming feature: he likes Dostoevsky

right about capitalism. Why not find something positive to say about a man whose ideology has been the inspiration for the most murderous, oppressive and evil regimes in human history. Rowan and Karl even look a bit alike – well Rowan needs to work on the beard. From the

right about capitalism. Why not find something positive to say about a man whose ideology has been the inspiration for the most murderous, oppressive and evil regimes in human history. Rowan and Karl even look a bit alike – well Rowan needs to work on the beard. From the  observed the way in which unbridled capitalism became a kind of mythology, ascribing reality, power and agency to things that had no life in themselves; he was right about that, if about little else. And ascribing independent reality to what you have in fact made yourself is a perfect definition of what the Jewish and Christian Scriptures call idolatry. What the present anxieties and disasters should be teaching us is to ‘keep ourselves from idols’, in the biblical phrase. The mythologies and abstractions, the pseudo-objects of much modern financial culture, are in urgent need of their own Dawkins or Hitchens. We need to be reacquainted with our own capacity to choose — which means acquiring some skills in discerning true faith from false, and re-learning some of the inescapable face-to-face dimensions of human trust.

observed the way in which unbridled capitalism became a kind of mythology, ascribing reality, power and agency to things that had no life in themselves; he was right about that, if about little else. And ascribing independent reality to what you have in fact made yourself is a perfect definition of what the Jewish and Christian Scriptures call idolatry. What the present anxieties and disasters should be teaching us is to ‘keep ourselves from idols’, in the biblical phrase. The mythologies and abstractions, the pseudo-objects of much modern financial culture, are in urgent need of their own Dawkins or Hitchens. We need to be reacquainted with our own capacity to choose — which means acquiring some skills in discerning true faith from false, and re-learning some of the inescapable face-to-face dimensions of human trust.