From here:

“What’s not widely understood is that the great majority of conservative Anglicans remained part of the diocese of New Westminster,” said Ingham. In fact, moderate conservatives and moderate progressives in the diocese worked to create provisions that no one should be compelled against their conscience to bless same-sex unions and to offer a visiting bishop to oversee parishes that were opposed to the decision. “I’m proud of the fact that a lot of people of goodwill on all sides came together and helped to make it work,” he said.

I doubt that the 800 people in St. John’s Shaughnessy who left the Diocese of New Westminster would agree that “the great majority of conservative Anglicans remained”. Those who did remain were tame conservatives who were duly paraded before synods as a demonstration of diocesan tolerance; no-one in the diocese actually listens to them, of course.

But the reaction was not confined to the diocese or even Canada. Same-sex blessings remain controversial in various parts of the worldwide Anglican Communion, but Ingham says New Westminster’s process of dialogue serves as an example for the Communion. Indaba conversations-an African model of respectful listening and dialogue-are now being used to help heal divisions in the Communion.

“If I have a word of advice, and I did actually say this to Rowan Willliams when he was the Archbishop of Canterbury,” said Ingham, “it is that these things do pass and you do someday find yourself on the other side of these passionate differences. And the way we deal with each other in the midst of them determines the quality of life of the community afterwards.”

To stoutly assert that the storm will soon be over as the church sallies forth into a bright new future of eco-harmony and prophetic social justice making, is a fondly-held liberal self-deception born of the blind optimism of arrogance.

I remember the Diocese of Niagara’s Bishop Ralph Spence in the 1990s peering mistily above the heads of his audience, presumably into a vision of the future that was impenetrable to the rest of us, intoning with an affected piety: “don’t worry about same-sex blessings; in ten years we will be performing them and the fuss will all be forgotten.”

Ingham has also worked to promote interfaith dialogues, including writing the book Mansions of the Spirit. “I’ve seen the whole church move from the attitude, ‘We don’t need to talk to people in other religions; we need to convert them,’ all the way to what I see as a predominant sentiment throughout the churches that we need to understand our neighbours of other faiths much better, because religion needs to be part of the solution, not part of the problem.” That has been increasingly relevant as awareness grows of how religion in its extremist and fundamentalist forms is a destabilizing and violent factor in so many parts of the world, he added.

One important challenge for the church moving into the future is Canada’s increasingly secular society, Ingham said. “Muslims and Jews and Buddhists and Hindus are not our competition. All of us, of all faiths, are seriously challenged by secularism, and we need to find a language that can address people whose understanding of the world is highly secularized, where there is no sense of God or the message of Jesus in their cosmology.”

This, in a way is good news. If Ingham and his successors see no need for converting people, the diocese will gradually wither away as congregations “understand our neighbours of other faiths much better”, realise that they actually believe something and convert to their beliefs. By the time the current generation joins the choir invisible, the diocese will be nothing but a disagreeable memory.

Like this:

Like Loading...

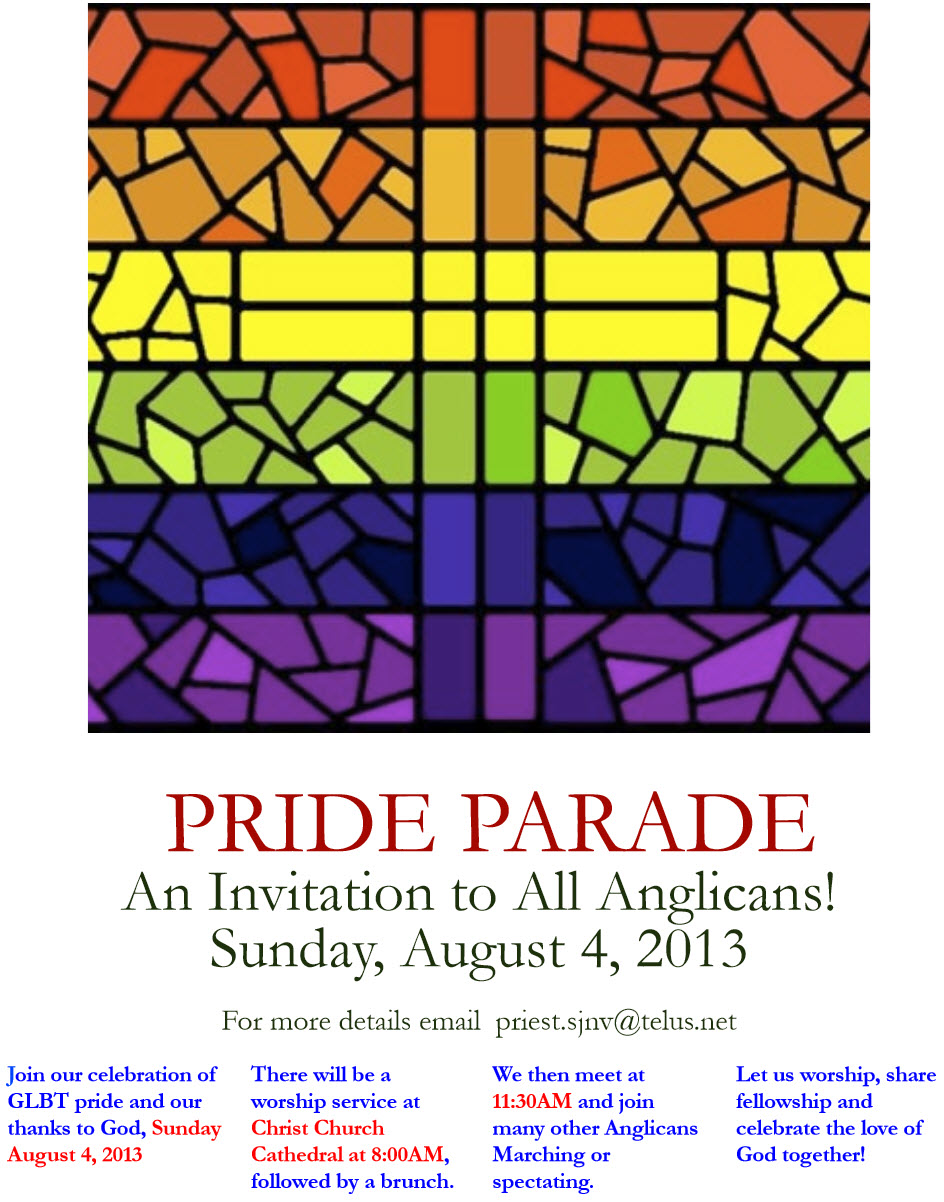

Celebrate God’s gift of diversity by marching with your Anglican sisters and brothers in the 2013 Vancouver Pride Parade!

Celebrate God’s gift of diversity by marching with your Anglican sisters and brothers in the 2013 Vancouver Pride Parade!