From the BBC:

The general synod of the Church of England has voted narrowly against the appointment of women as bishops.

The measure was passed by the synod’s houses of bishops and clergy but was rejected by the House of Laity.

Supporters vowed to continue their campaign but it will be five years before a similar vote can be held.

Controversy had centred on the provisions for parishes opposed to women bishops to request supervision by a stand-in male bishop.

The outgoing Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, spoke of his “deep personal sadness” after the vote.

He said: “Of course I hoped and prayed that this particular business would be at another stage before I left, and course it is a personal sadness, a deep personal sadness that that is not the case.

“I can only wish the synod and the archbishop all good things and every blessing with resolving this in the shortest possible time.”

Both the archbishop and his successor, the Rt Rev Justin Welby, were in favour of a “yes” vote.

I’ve always been ambivalent about lady bishops and priests. It does seem to me though, that if one is permitted – there are women priests in the CofE – then it’s much harder to make a convincing case against the other.

I do think there is a stronger Biblical case to be made against women priests than for them, that the introduction of women priests after 2000 years of not having them, means we need a very good case for them that transcends the Zeitgeist, and the desperation with which many ladies demand ordination as their right leaves me queasily suspicious of their calling.

C. S. Lewis had one of the more cogent arguments against what he called priestesses:

At this point the common sensible reformer is apt to ask why, if women can preach, they cannot do all the rest of a priest’s work. This question deepens the discomfort of my side. We begin to feel that what really divides us from our opponents is a difference between the meaning which they and we give to the word “priest”. The more they speak (and speak truly) about the competence of women in administration, their tact and sympathy as advisers, their national talent for “visiting”, the more we feel that the central thing is being forgotten. To us a priest is primarily a representative, a double representative, who represents us to God and God to us. Our very eyes teach us this in church. Sometimes the priest turns his back on us and faces the East – he speaks to God for us: sometimes he faces us and speaks to us for God. We have no objection to a woman doing the first: the whole difficulty is about the second. But why? Why should a woman not in this sense represent God? Certainly not because she is necessarily, or even probably, less holy or less charitable or stupider than a man. In that sense she may be as “God-like” as a man; and a given women much more so than a given man. The sense in which she cannot represent God will perhaps be plainer if we look at the thing the other way round.

Suppose the reformer stops saying that a good woman may be like God and begins saying that God is like a good woman. Suppose he says that we might just as well pray to “Our Mother which art in heaven” as to “Our Father”. Suppose he suggests that the Incarnation might just as well have taken a female as a male form, and the Second Person of the Trinity be as well called the Daughter as the Son. Suppose, finally, that the mystical marriage were reversed, that the Church were the Bridegroom and Christ the Bride. All this, as it seems to me, is involved in the claim that a woman can represent God as a priest does.

Now it is surely the case that if all these supposals were ever carried into effect we should be embarked on a different religion. Goddesses have, of course, been worshipped: many religions have had priestesses. But they are religions quite different in character from Christianity. Common sense, disregarding the discomfort, or even the horror, which the idea of turning all our theological language into the feminine gender arouses in most Christians, will ask “Why not? Since God is in fact not a biological being and has no sex, what can it matter whether we say He or She, Father or Mother, Son or Daughter?”

But Christians think that God Himself has taught us how to speak of Him. To say that it does not matter is to say either that all the masculine imagery is not inspired, is merely human in origin, or else that, though inspired, it is quite arbitrary and unessential. And this is surely intolerable: or, if tolerable, it is an argument not in favour of Christian priestesses but against Christianity. It is also surely based on a shallow view of imagery. Without drawing upon religion, we know from our poetical experience that image and apprehension cleave closer together than common sense is here prepared to admit; that a child who has been taught to pray to a Mother in Heaven would have a religious life radically different from that of a Christian child. And as image and apprehension are in an organic unity, so, for a Christian, are human body and human soul.

The innovators are really implying that sex is something superficial, irrelevant to the spiritual life. To say that men and women are equally eligible for a certain profession is to say that for the purposes of that profession their sex is irrelevant. We are, within that context, treating both as neuters.

As the State grows more like a hive or an ant-hill it needs an increasing number of workers who can be treated as neuters. This may be inevitable for our secular life. But in our Christian life we must return to reality. There we are not homogeneous units, but different and complementary organs of a mystical body. Lady Nunburnholme has claimed that the equality of men and women is a Christian principle. I do not remember the text in scripture nor the Fathers, nor Hooker, nor the Prayer Book which asserts it; but that is not here my point. The point is that unless “equal” means “interchangeable”, equality makes nothing for the priesthood of women. And the kind of equality which implies that the equals are interchangeable (like counters or identical machines) is, among humans, a legal fiction

The defeat of the motion in the CofE synod is a nasty blow for Rowan Williams – who strongly supported it – and, potentially, for his replacement, Justin Welby who now has to deal with Rev Rachel Weir and her ilk, whose desire to have synodical blessing on what appears to be an unseemly ambition to claw one’s way to the top has been thwarted. For five years, at least.

From

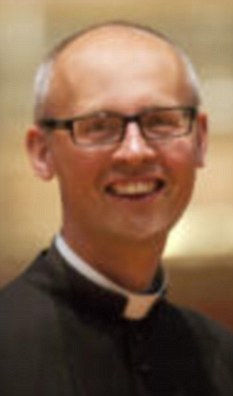

From  To celebrate Easter, Father Phil Ritchie recommends staying in bed, eating chocolate and copulating – because going to church isn’t “cool and funky”; whether this has to be done simultaneously is unclear.

To celebrate Easter, Father Phil Ritchie recommends staying in bed, eating chocolate and copulating – because going to church isn’t “cool and funky”; whether this has to be done simultaneously is unclear.