Apparently, indabas have been replaced by sankofas – and you can tell what that reminds me of by the title.

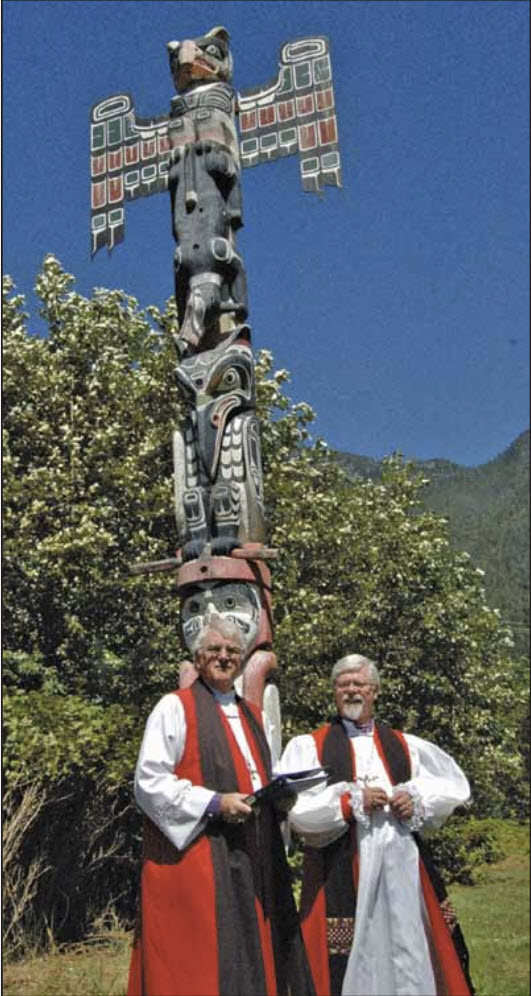

But I jest. Sankofa actually means: “It is not a taboo to fetch what is at risk of being left behind”. It is a catchphrase taught to English bus drivers to be used as they watch old ladies in their rear view mirrors running after the bus. If that isn’t clear enough, the definition goes on to say: “the narrative of the past is a dynamic reality that cannot be separated from consideration of the present and future”. In other words, the past is dynamic, or changeable by the present, a concept made popular in the ‘70s by those consuming an excessive quantity of magic mushrooms. Since Canadian bishops seem to fall into that category, many of them – Hiltz, Bird, Ingham and Alexander – were present at the latest salacious sankofa exercise to ponder together homoerotic sexuality under the pretext of conjuring a prior dynamic reality that conforms ancient perversions to 21st century delusions of normalcy.

A pusillanimous church – and that’s what Western Anglicanism has become – grovels and trembles before the culture in which it finds itself. Hence, as Ingham notes below, the church is content to let the culture determine its theology. A church can sink no lower than that.

From here:

Introduced by the Most Rev. Prof. Emmanuel Asante as an ecumenical contribution from the Methodist Church of Ghana, the Akan concept of sankofa served as a guiding framework for the Seventh Consultation of Anglican Bishops in Dialogue, which took place from May 25-29 in Accra, Ghana. The gathering brought together bishops from Canada, Ghana, Swaziland, Tanzania, Kenya, South Africa, Burundi, Zambia, England, and the United States.

Sankofa—literally, ‘It is not a taboo to fetch what is at risk of being left behind’—refers broadly to the unity of past and present, where the narrative of the past is a dynamic reality that cannot be separated from consideration of the present and future.

[….]

Bishop Ingham noted that despite the bishops present holding many different theologies on marriage, sexuality and biblical interpretation, “we’re not divided by these differences. Rather, we’re spurred to be curious with each other and to hear how these matters play out in our different parts of the world.”

“We’re all very aware that mission is contextual,” he added. “And I think most of the African bishops who attend understand that social and legislative challenges have taken place around homosexuality in Western countries.

Those who wish to be regaled with tales of Ingham’s former triumphs – or how to break up a worldwide denomination by being inclusive – may do so for a mere $225. I wonder how much Ingham is being paid.

Those who wish to be regaled with tales of Ingham’s former triumphs – or how to break up a worldwide denomination by being inclusive – may do so for a mere $225. I wonder how much Ingham is being paid.