A Church of England parish is hosting The Sunday Assembly, whose vision is: “a godless congregation in every town, city and village that wants one.”

From here:

St John the Evangelist in Leeds can rarely have hosted such an ungodly meeting.

The Sunday Assembly – dedicated to providing “the best of church but without God” – was on the latest stop of its UK tour.

Spilling out through the open door of the 400-year-old church came voices united in a rendering of Queen’s Don’t Stop Me Now.

Inside, a couple of hundred people – average age about 35 – clapped rhythmically, swaying in the venerable pews.

[….]

The event is a brazen copy of a church service.

As well as emotional and uplifting songs, there was a talk from a woman who had turned her life around by volunteering, another from a scientist about the human propensity to misperceive reality and a minute’s silent reflection.

During a rendering of Dire Straits’ Walk Of Life a collection was taken.

“We both wanted to do something like church but without God and we just nicked the order of service,” admits Mr Jones.

A Church of England vicar was in attendance to pick up tips for developing a nuanced view to the more crass beliefs of Christianity, stumbling blocks such as the Virgin Birth and Resurrection:

Canon Adrian Alker’s job is to attract people like Andy to the Church of England by fostering imaginative new ways for it to practise and explain Anglican Christianity.

He accepted that many in the Church’s target audience have become disenchanted with what they perceive to be compulsory but dubious doctrines – such as a belief in the birth of Jesus to a virgin and that Jesus was physically resurrected from the dead.

Canon Alker said the answer was not for the Church to place less emphasis on God, but actually to make more effort to explain a more nuanced idea of what God was.

“I think doctrine does develop,” he said. “It wasn’t born in Palestine 2,000 years ago. I think there should be open discussion, and [there] often is, about these core elements of the Christian faith.”

Canon Adrian Alker doesn’t seem to realise that we have already tried that in Canada. The Sunday Assembly bears an eerie resemblance to – not just a tofu hamburger – the Anglican Church of Canada. It:

- Has no doctrine.

- Is radically inclusive. Everyone is welcome, regardless of their beliefs – this is a place of love that is open and accepting.

- We won’t tell you how to live, but will try to help you do it as well as you can.

- Most of all, have fun, be nice and join in.

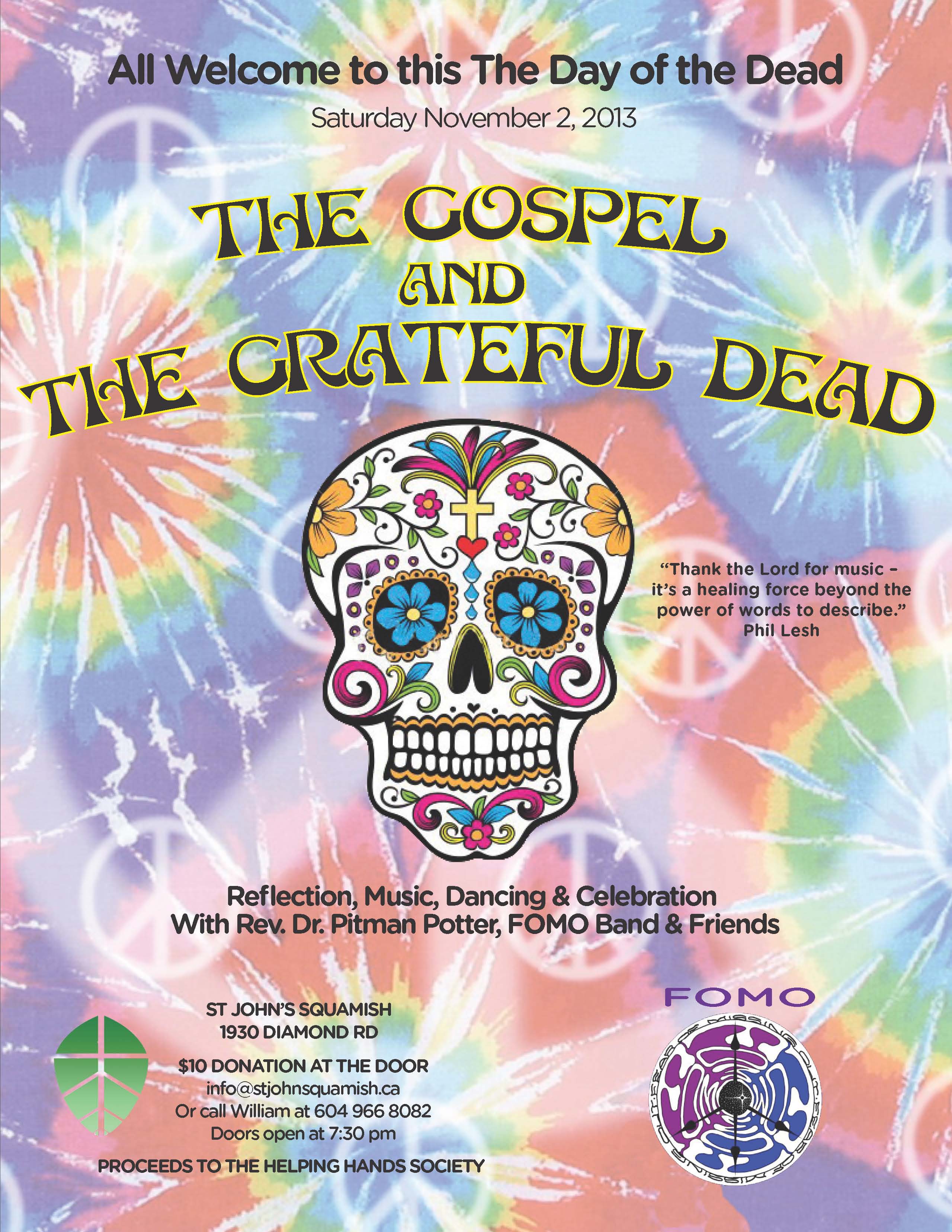

muertos” November 2? It is a holiday that celebrates friends and family members who have died. It is celebrated in Spain, Brazil and Mexico and in cultures around the world with festivals and parades, sugar skulls and marigolds and favourite foods and beverages of the departed and visiting graves with these as gifts. It is the perfect occasion for St John’s to welcome the wider community to an evening of reflections by Pitman Potter, singing Grateful Dead songs with FOMO and friends, dancing together in spirit, and raising money for The Helping Hands Society.

muertos” November 2? It is a holiday that celebrates friends and family members who have died. It is celebrated in Spain, Brazil and Mexico and in cultures around the world with festivals and parades, sugar skulls and marigolds and favourite foods and beverages of the departed and visiting graves with these as gifts. It is the perfect occasion for St John’s to welcome the wider community to an evening of reflections by Pitman Potter, singing Grateful Dead songs with FOMO and friends, dancing together in spirit, and raising money for The Helping Hands Society. Rituals celebrating the deaths of ancestors had been observed by these civilizations perhaps for as long as 2,500–3,000 years. In the pre-Hispanic era skulls were commonly kept as trophies and displayed during the rituals to symbolize death and rebirth.

Rituals celebrating the deaths of ancestors had been observed by these civilizations perhaps for as long as 2,500–3,000 years. In the pre-Hispanic era skulls were commonly kept as trophies and displayed during the rituals to symbolize death and rebirth.