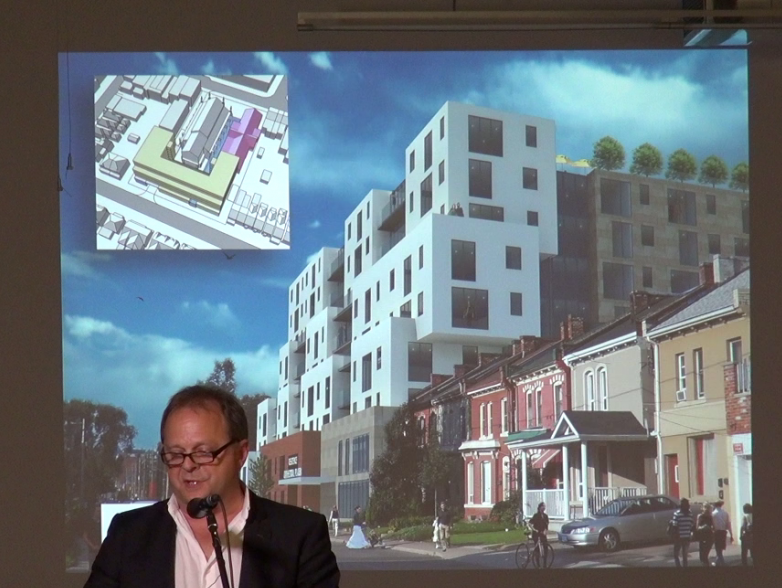

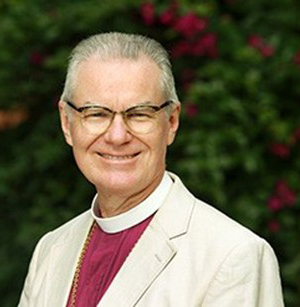

George Sumner is presently a member of the Anglican Church of Canada and Principal of Wycliffe College, University of Toronto. I interviewed him in 2010 during the ACoC General Synod; much of what we talked about related to the synod itself but, considering his election, the conversation might be of interest to some, so here it is in full:

David: Is there a particular issue facing the Anglican Church of Canada that needs to be addressed by this synod and, is it being addressed?

Rev. Dr. George: The synod is going to talk about the Covenant; it’s most likely they will initiate and commend a period of study of the Covenant; it might have had more attention – perhaps in the coming triennium it will get the attention it deserves.

David: Will that be too late?

Rev. Dr. George: I don’t think it’s too late but I do think that in the meantime it’s important that the church take it seriously in those 3 years, that people would think about it. The Covenant ought to be more than simply a legislative act of acceptance or rejection: it ought to inform and help and that is something you hope would happen in dioceses and parishes. I think the bonds of affection globally are important for our identity as Anglicans, it’s integral to our identity as catholic Christians.

David: I have a few friends who went through seminary – not Wycliffe – entering as Christians and emerging as something else. The ones who were still Christian when they came out had to spend much of their time trying to hang on to their faith in spite of all efforts to subvert it. Why on earth is that happening? Any comments?

Rev. Dr. George: It depends what you think theological education’s task mandate is. Our faculty share a Nicene faith. We hope we are contributing to the upbuilding of the church, the edification of the church in its Nicene faith. What theological education is supposed to be is a particular way of building up leaders who can catechise, who can convey that same faith to other Christians. So, to us, it’s a misunderstanding of theological education to think its primary task is to destroy the Nicene faith – and some theological education imagines itself to be that. The way you avoid that is though serious theological work on the traditional doctrines of the church: the atonement; sin – a kind of education that understands itself to be for the forming of leaders to be ordained for actual ministry in the church. You’re trying to close the gap which can arise between the practice of church and theology. But, to be an evangelical school is to do that theological work not only for church, but in the service of the Gospel. That takes a certain kind of focus: theology is meant to be the guarding, clarifying and testing of the faith of the church according to the Scripture. Is theological education always that? No.

David: In some seminaries, it appears not to be.

Rev. Dr. George: Well, I’m an evangelical, so I would advocate that it should be. I’m a member of the Anglican Church of Canada and live and minister to upbuild and support the ACoC; I think there is a particular contribution that theology has to make and a particular contribution that more traditional Anglicans and evangelical have to make, That’s really important to bear in mind because synods have their own place, they come and go, but the ongoing deeper work of catechesis in a culture which is increasingly de-Christianised, in a church which is often forgetful of roots, that really matters. Synods are one thing, but at a grass roots level there have to be leaders who can teach the faith.

David: That leads me to another question: you are trying to produce leaders who can make disciples. I’m not anti-intellectual, but if Jesus had spoken to the thief on the cross using the terminology and language of some of your professors, he would have – had he been able – scratched his head, turned to the other thief and said, “what did he just say?”

Rev. Dr. George: I think theology isn’t the same thing as preaching: preaching is a first order activity – you are communicating the Gospel to people, but theology is meant to step back and think about how we’re doing that. So the professors you are referring to would agree about the moment of witness – which is the analogue of when Jesus was talking to the thief. There was a church where I did doctoral study to which would come all these famous professors and I remember the pastor there would say that he had to remind himself, as he ascended the pulpit, that every one of them was a dying sinner. You’re right, you’re training people to do that, but in the service of that there’s a place for thinking about what the church is, what our doctrine is – we live in a church which spends very little time actually thinking about doctrinal questions. And we’re not always well served by that.

David: So my lingering suspicion that it’s obscurity for obscurity’s sake is really not founded then?

Rev. Dr. George: I think it isn’t because one of the fruits of one of the professors you are probably thinking of was serving on the committee that wrote the Covenant – really trying to fight his way to know what it means to love the church, and to suffer with the church and also to witness to it.

David: Do you think that, for some, there is a desire to cling to Anglicanism and all its trappings more than to Christianity or Christ – that Anglicanism has become so important that compromises are being made that shouldn’t be made and that Anglican unity has been set at a higher priority than truth?

Rev. Dr. George: My assumption is that there is an important and valuable dynamic in having movements of theological witness and renewal within the church catholic. And the danger to the church catholic is forgetfulness or having its life centred on self. That kind of inertia is always the danger: churches need movements of renewal within them to remind them that they exist for the sake of the Gospel. And in Anglicanism in the modern period, that was the catholic as well as the evangelical: the Anglo Catholics and the evangelicals were movements that stayed within the church that was forgetful in its own way in the nineteenth century and were meant to remind it of something larger for which it existed. Evangelicals would say that the church is always in danger of making its own existence the reason for its being. We even do that in our own lives of faith.

David: George Orwell said, “the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts.” Every second sentence in this synod has included “missional”, “mission”, “spirit” and so on. I suspect the people using these words mean something different than I would mean if I used them, or, perhaps they have no idea what they mean by them.

Rev. Dr. George: Yes, I agree with you. One of the challenges is that if a church says, we need to have a more mission focussed life, there is no appropriate answer but, “amen”. Who would be against that? And there are many ways in which we would applaud that. Sometimes we wake up to some evangelistic imperative out of practical concerns but, for whatever reason, if the Gospel is preached that is good. However, I think you are right that, it’s one thing to say that our idea of mission has to be wider and that could include social transformation and activism, but there is a difference between saying that and saying social transformation and activism is the Gospel. John Stott talked about holistic mission which was both evangelistic and involved social witness – that’s a good thing. The test is, does the idea of mission include the hope and expectation of witnessing to people who would come to faith in Jesus Christ. It’s become the coin of the realm.

David: Yes, and the point I’m getting at is when someone uses the word “mission”, I have no idea what they mean.

Rev. Dr. George: And the litmus test I would offer would be, if what they’re describing includes, in a central way, Christians witnessing to their faith in Jesus Christ, in the hope that by the grace of God that person might come to believe, then the odds are pretty good they’re talking about some kind of wider expansive view of what mission is and not something else.

David: “Spirit” is another word that seems to be misused. KJS made the rather strange point in her Pentecost letter that different people are hearing different messages from the Spirit. Surely the Spirit would not give different messages on the same subject depending on the “context”.

Rev. Dr. George: I bet you, if you were to press Bishop Schori, even she would say we may be at different stages of hearing; my guess is she has a notion about what the Spirit is ultimately saying. I suspect she may have some notion of the unfolding of geist in history that’s moving somewhere. So the language of context serves in a certain situation, but she’s got a destination.

David: What I’m getting at is that people seem to be using “spirit” as an excuse to validate their own thinking.

Rev. Dr. George: Well I think some users of “spirit” have in mind a certain idea of history; traditionally for the church the test was that the work of Persons of the Trinity is indivisible, so the church traditionally tested the spirits by the canon of Scripture and the movement of the Spirit moves towards Jesus Christ. I think there is an invocation of the Spirit on behalf of charity and trying to overcome conflict, so I’m sympathetic to this: I think it’s true that, where the Spirit is, there is charity. It’s also true that Christians have traditionally taken the witness of the Holy Scripture as the canon rule by which they determined which spirit is speaking.

David: Do you think the idea of “inclusion” has become an idol?

Rev. Dr. George: I think that what our secular age longs for is a kind of shadow or fragment of what the Gospel actually offers. In other words, we long for inclusion; what the Christian Gospel offers is the hope of the Kingdom of God first of all and it offers in the meanwhile the joining together of all nations of the earth in the Church. So the secular longing for inclusion has a response in the catholic nature – the global – nature of the Church.

David: But I meant is it an idol in the church.

Rev. Dr. George: The Anglican Communion is inclusive and diverse and in cities of Canada you see a remarkable gathering of the people of the earth in worship. So, as someone who is interested in mission, there’s a valid kind of inclusion, which is the gathering of all the peoples of the earth. The culture’s more general reaching after this is less focussed.

David: I dug up some numbers of how many people attended the ACoC over the years: in 1961 it was 1.2M, in 2001, 625,000 and in 2009, 325,000. If you plot a graph, that gives you zero in 2040.

Rev. Dr. George: There is a widespread awareness and worry among contemporary Canadian Anglicans about that.

David: Yes – a little while ago I was talking to a professor of church history – one of yours. He takes a very long view of things. I didn’t bring these figures up with him, but we did discuss ANiC and why some churches thought they had to leave. In his long view, he believed that the ACoC could return to orthodox Christian belief, so it’s worth remaining in the ACoC. But if the numerical decline continues, there won’t be anything left to come back.

Rev. Dr. George: the church may well need to reorganise itself and downsize. But the real work is evangelistic and catechistic: the church seems to have lost a generation and it has to be a church that can find old and new ways to convey the faith. That is what we exist to do and I would emphasis that that is why the church needs to find an important place for its evangelical mandate.

David: That’s what you’re trying to do.

Rev. Dr. George: Yes, whether it be something more traditional or Fresh Expressions, whatever modality, people who have a burden for evangelisation and for catechesis are often traditional Anglicans – which is not to say they are the only ones who do this, but they have a very particular and important role and that is the real task ahead of us. That being said – as we talked about yesterday – I do think that the church is usually dying and being born; I think there is still considerable attraction in the notion of being evangelical in a catholic Christian mode.

David: I don’t have to be convinced of that.

Rev. Dr. George: So I think, as Mark Twain said, “Reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated”. I agree with you 100%: there are dire statistics which the church would ignore at its peril. At the same time there is something here that, for all its confusion, is worthwhile.

David: African churches have been sending missionaries to North America. Is this a good thing?

Rev. Dr. George: I think the missiological slogan, from 6 continents to 6 continents is a good thing and it undoes some of the presumption about the movement of people and resources from the West to the global south. It’s complicated – being a Nigerian or South Korean or Ugandan coming to North America is not a culturally easy thing. To give you an example: I was ordained in Tanzania and still stay in touch with my friends there – and it is a normal expectation for a parish to plant a church yearly. Now is that a fair expectation here for every rector? No, not in our culture. But is that a good wake-up call and challenge? Yes. In East Africa they thought about the structure of the church in a way that made sense evangelistically and catechistically: there weren’t that many ordained clerics but the were lots of people who would still plant churches. So they had a structure – and they were evangelicals so this came naturally to them – which was conducive to these things. It would not be a bad thing for us to be challenged to think about what kind of structure we need.

David: I talked to another of your professors about Fresh Expressions. The concern I raised was what would the techniques he was teaching be used to express – would it be the Gospel?

Rev. Dr. George: I think encouraging the church to let many flowers bloom evangelistically is good. You know, the flowers will thrive or they’ll die – like the parable of the sower. The fact that the professor in question himself is a theologically grounded is not irrelevant. These things are not just techniques – the Gospel is never a technique.

David: My point is that that was all very well, perhaps, while he was still involved, but once it was handed over to a less than orthodox diocese, it would no longer be a Fresh Expression of the Gospel, but something else.

Rev. Dr. George: Maybe I’m an optimist.

David: I’m not accused of that very often.

Rev. Dr. George: I think there is a felicitous version of the law of unforeseen consequences: you scatter these things and what God can do with them is maybe surprising. Is there a potential that it it could become a mere technique? Sure, but there’s also the potential that….

David:… something good could stick anyway.

Rev. Dr. George: I think so. And you know, Fresh Expressions was a child of the evangelical wing of the Church of England, so to understand it requires remembering the soil from which it springs and that in some ways is as important as the actual technique itself.

David: Going back to an earlier point where I mentioned that the professor of church history took a long view of what is happening in the ACoC: it’s one thing to take a long view in an academic sense, but for the average ANiC parishioner, all they want is to be part of an organisation that has the same religion as them – right now. What other practical option is there than to get out?

Rev. Dr. George: Obviously I’m someone who believes that there is a valid calling to remain in the ACoC and to work for and be hopeful of its renewal. And I believe that the ACoC in its formal prayer is an orthodox church.

David: You haven’t attended any Diocese of Niagara synods, have you?

Rev. Dr. George: You go back to Melancthon – wherever the Gospel is truly preached and the sacraments rightly administered; I think that scope remains. At the same time – and I understand that this may not be how it looks to lay people – I would agree with my colleague about taking the long view. The evangelical movement within Anglicanism began in the early 19th century in England, when, in many ways, the church seemed moribund. So I think that option still remains, but I share the traditional view of the doctrine of Christian marriage and realise that that poses challenges for Anglicans in the ACoC. My hope is that in the long term the evangelical witness will prove to be important.

David: OK, well let me take an extremely long view, then: the final destination of our immortal souls. If one believed that by remaining in a diocese that is less than orthodox it could jeopardise the souls of the parishioners, would that be a justifiable reason for leaving? Hypothetically.

Rev. Dr. George: All of us would agree that we have to take a somewhat long view. To give an extreme example, no-one would leave a parish every time the rector came up with some wacky notion. But the real question is that, for Reformation Christians, the article on which the church stands or falls is justification: as sinners are we saved by the grace of God in the sacrificial death of Jesus Christ. A church where that can be heard is – a church. It may be a sleepy church or a confused church. There comes a limit case, an extreme case, where you can no longer recognise Christianity in a church, so I’m not saying that there could never be such a case. I don’t think that’s where we are; I think the prayer books of the church are recognisably Christian. My exhortation to conservative Anglicans in Canada is to set about the business of building up parishes, dioceses and schools and understanding themselves as servants of the renewal of the church.

David: I presume you’d agree with the assertion that the fact that some conservatives have left the ACoC has probably weakened the conservative cause within the ACoC.

Rev. Dr. George: Well, yes, obviously there are fewer of us. It’s not my place to judge. These people were all friends, so one hopes that continues.

David: Has the friendship been broken by what’s happened?

Rev. Dr. George: Institutions make most sense when they are functioning well – properly. When things break down everyone is placed into various kinds of conundrums and that’s stressful for everybody. I can only speak for the particular kind of vocation of those who remain within this branch of the church catholic.

David: The issue that seems to have caused the split appears to be same-sex blessings. It seems to me that underneath that there are worse problems – it goes back to the meaning of words again. For example, I’m moderately convinced that when I say I believe in Jesus’ Resurrection it doesn’t mean the same as when some clerics might say it; if probed a little, it becomes quite clear that we don’t mean the same thing at all. That is a bigger problem than same-sex blessings. It’s the same for the Virgin birth, many clergy don’t believe in it, yet, not believing undermines the whole logic of Christianity – it all starts falling apart. How can church leaders be talking and believing such nonsense?

Rev. Dr. George: One of the interesting offshoots of the same-sex debate was the agreement of the ACoC in its theological commission with the point you’re making. The primate’s theological commission – whatever one doesn’t like about the distinction between core doctrine and doctrine – was at least saying that. That there are things whose denial are problematic straight away. And you’re right…. in the debate, that was used as a way of saying the same-sex issue isn’t so big a deal because it’s not that [core doctrine]. So one of the offshoots would be to say, if you hold one of those views of denying a central creedal point – that would be out of bounds. That always interested me; although I’m not sure that everyone followed that trajectory. That being said, it isn’t true that just because something isn’t in core doctrine that it doesn’t touch on important doctrinal matters. One of the reasons the whole debate is unfortunate is it’s a symptom of these deeper wider problems. Moderns have an idea of autonomy which renders some of these traditional moral commitments difficult; it’s hard for moderns to really make sense of the doctrine of sin. Those are pervasive questions that come to express themselves in a variety of ways. The desire for tolerance and charity, which is part of this whole thing – that’s a good impulse. The notion that everyone who comes through the door is broken in some way or other is just Christian doctrine.

David: In some cases it’s difficult to pin down what a liberal believes, but in others, it’s quite clear. There is at least one bishop who has stated he doesn’t believe in the Resurrection in the orthodox sense. So we have a church which allows a bishop to disseminate beliefs that are contrary to those of the church he belongs to; there’s something radically wrong, isn’t there? It would be like an executive from McDonald’s preaching on the virtues of vegetarianism.

Rev. Dr. George: The only answer is the vigorous support of Anglican theological colleges and their theological work.

David: I wanted you to say he should be booted out.

Rev. Dr. George: (laughing) And I wanted to give my pitch.

David: Carry on with your pitch.

Rev. Dr. George: At the end of the day the church needs those peculiar communities of scholars who are prepared and able to articulate the Nicene faith in a winsome and coherent way.

David: Diversity also seems to have become something of an idol. Diversity in, say, style of worship – style of almost anything – might not be a bad thing. Now, though, it seems that diversity also includes heresy. We are a church that is so diverse that we even encompass things we are not supposed to believe.

Rev. Dr. George: There’s no getting around the fact that the books of the Old and New Testament are Scripture in the sense that they are a norm for the church’s life. That doesn’t remove the necessity for reading and interpreting them; that can be done with the normative guidance of tradition. There will be arguments about what they mean, but the question of the limits of diversity leads inexorably to the hearing of Scripture as an authority for the life of the church.

David: Quite a few years back, I met J. I. Packer and asked him, “What’s gone wrong?” He said one of the problems is that theologians stopped believing that Scripture is God’s propositional revelation. When I met him recently and reminded him of that, he said he wouldn’t necessarily put it quite that way now.

Rev. Dr. George: I think he would probably agree with this: to be a Nicene Christian requires that one be a realist in the sense that one believes that the words the tradition has used to describe the world conform to how the world really is. That is propositional in the wider sense. And it requires some kind of doctrine of perspicuity, that is to say, the Scriptures can be heard. There are hard bits and one verse bumps against another but, at the end of the day, what matters most is clear; and that it can be read as a whole. Both of those statements have some relation to the idea of assertion: I think Dr. Packer is being careful because it’s harder to claim that some things are propositions than others when you read the Bible. But it can assert how the world really is and it can do so clearly and coherently – those are things you need to be able to say.

David: Is part of the problem in the ACoC caused by the fact that we no longer believe that?

Rev. Dr. George: Allowing for the fact there will be debate about interpretation, where the Bible does not so function – where that isn’t true – the church will be left to its own devices. And it will struggle to find criteria that are truly edifying.

David: Thank you very much.

Rev. Dr. George And thank you very much.

Like this:

Like Loading...

From

From